Dunedin and the Otago Peninsula

When we made the decision to come to New Zealand I went and bought a couple of guide books. While there is an immense amount of information available online, I still find that using an actual book is often easier than clicking back and forth between a bunch of tabs in Google Chrome. It also narrows the scope of author and reader. The author is definitely well-versed in the country they are writing about and the intended reader is someone who has most likely never been to the country. Whereas there are definitely some websites about New Zealand that are written by people that have spent very little time there. The guidebooks also cover topics that are only important to outsiders, such as should you tip at restaurants, what is a roadside bathroom like, and how much do milk and bread cost.

One of the big things that all the NZ guidebooks emphasized was how different it is to drive and go on road trips there compared to the US. First, you have the immediate change to driving on the left side of the road, which also entails the driver sitting on the right side of the car and all the instrumentation and controls also being flipped around. Even after three weeks of driving here I still occasionally turn on the windshield wipers instead of my turn signal. Then, you have the change to metric measurement so everything is in kilometers instead of miles. Going 100 kph is the equivalent of going 62 mph and 120 kph is 74 mph. Beyond those two changes, the other huge difference is the type of roads you find in NZ, especially outside the major cities. We have been here for three weeks now and I have yet to see a four lane road. State roads (NZ version of an interstate) are two lane roads that rarely are straight. They occasionally go to three lanes wide for passing, but otherwise for Cameron and I it’s no different than driving on the two lane rural roads where we grew up. That familiarity of a winding, rolling, two-lane road made it an easier transition for us than it may have for someone who grew up in a city. But, the part that we are really not used to is driving four hours on a road like that to travel 180 miles all while exercising immense self-control to keep your eyes on the road and not take in all the amazing scenery. The final big warning the guidebooks give is to avoid driving unfamiliar roads at night. Since the sun sets around 6:30 in Wanaka that shortens our potential travel time. It may seem overly cautious to not drive at night, but the thought of having to deal with the consequences of something bad happening when we’re far from home makes us that way.

So, when a guidebook warns that you can’t plan your travel in NZ with an American mindset it really means it. Trusting that the guidebooks knew what they were talking about we had to rethink the scope of our travel while in NZ. Back home in North Carolina we wouldn’t think twice about doing a 300 mile day trip, driving the back half home after dark in order to extend the day. Applying that logic to NZ we could do a ton of day trips from Wanaka and visit lots of the highlights of the South Island. Adjusting for the reality of driving in NZ meant that our day trip radius was cut in half. To compensate for that change we decided to do some overnight trips to places we really wanted to visit and also had to accept that we would have to cut some places off our list. We decided that we would do three one night trips to Dunedin, Fox/Franz Josef Glacier, and Milford Sound. Once we were settled in Wanaka we started to watch the weather for those places and make tentative plans.

Not long after we got to Wanaka an unusual weather pattern developed that pulled subantarctic air away from Antarctica and swirled it up over all of New Zealand. Even though it was the first week of spring here it still felt a lot like winter with temps in the lower 40’s and gusty winds. All three of the overnight trips we wanted to do involved extensive time outside so we knew we needed to hope and wait for things to warm up. We kept a close watch on forecasts and things were looking okay in Dunedin so we went ahead and booked a hotel and kept our fingers crossed that the weather would hold out for us.

Dunedin is a harbor city of 117,000 people on the southeast coast of the South Island. It is home to a large port and the University of Otago. It is protected from the Pacific Ocean by the Otago Peninsula, which is a remarkably serene and undeveloped stretch of land that is the home to some of New Zealand’s most precious wildlife. Dunedin and the Otago Peninsula deserve at least 3-4 days to truly appreciate, but since we had about 36 hours available we packed in as much as we could. The drive to Dunedin is about 3.5 hours through Central Otago, which is largely an agricultural region. That drive certainly reinforces the euphemism that the sheep outnumber the people in NZ (in fact the latest data shows the sheep to person ratio is 7:1). It’s beautiful country and reminded me a little of the area in the Shenandoah Valle of Virginia where I grew up. We left Wanaka mid-morning and made it to our first stop, Tunnel Beach on the southern end of the Otaga Peninsula, early in the afternoon. After a short, but steep, walk down a brush-covered hillside we made it to the tunnel for which the beach is named. Built by a man who wanted his family to be able to access the beautiful, isolated spot the tunnel is a narrow set of stairs carved through the hillside that opens onto a sheltered, rocky section of beach around 40 yards wide. We were there on a cool, windy day at high tide so the water was quite rough and not a spot I’d think of as appropriate for kids, but I’m sure at low tide on a calmer day that sheltered cove makes it feel like you’re the only people in the world.

After hiking back up to our car we turned north and started the drive out to the northern tip of the Otago Peninsula where we were going on a guided tour of a reserve for endangered yellow-eyed penguins. These penguins, along with Albatross, Sea Lions, Fur Seals, Blue Penguins, and many other wildlife, find refuge on this little stretch of land at the bottom of the world. There is great pride in Dunedin and the surrounding area that as a people they have decided to protect and preserve the peninsula for its wildlife inhabitants instead of allowing it to be developed and exploited. Penguin Place is a preserve on the peninsula that is completely funded by tourism and is the sole rehabilitation facility for any injured yellow-eyed penguin in New Zealand. The tour started with an information session on the penguin and the current state of its precarious existence. While the preserve is certainly doing everything it can to protect this species, the prognosis is not good, especially if there isn’t change in the fishing industry or a slowdown in the rise of the water temperature where the penguins find food. After the information session we went into the reserve where we hoped to observe some of these penguins from blinds that are built into the side of hills and hidden by vegetation. Our guide had told us he hoped we would see 1-3 penguins and that if we saw five or more we were quite lucky. We ended up spotting seven yellow-eyed penguins and they were as adorable and impressive as you would imagine. I encourage you to read Ada’s blog for more details on our visit to Penguin Place as it had quite an impact on her.

After our tour we drove back down the peninsula into Dunedin to our hotel for that night. Not long after making it into the city Jackson commented that Dunedin reminded him of San Francisco because it was so hilly. While the harbor and downtown are right on the water, the city spreads out and up around it. Some the streets are so steep that we were actually laughing at how ridiculous it was as we drove up them. We got checked into our room and then went in search of a warm meal after spending all afternoon outside in the cold and wind. The next morning we went down to the Octagon, the city center of Dunedin, for breakfast and then worked our way through some of the must see spots in the city. We started at the Dunedin Rail Station and the New Zealand Sports Hall of Fame. We then visited the Dunedin Art Gallery and the Otago Museum on the university campus.

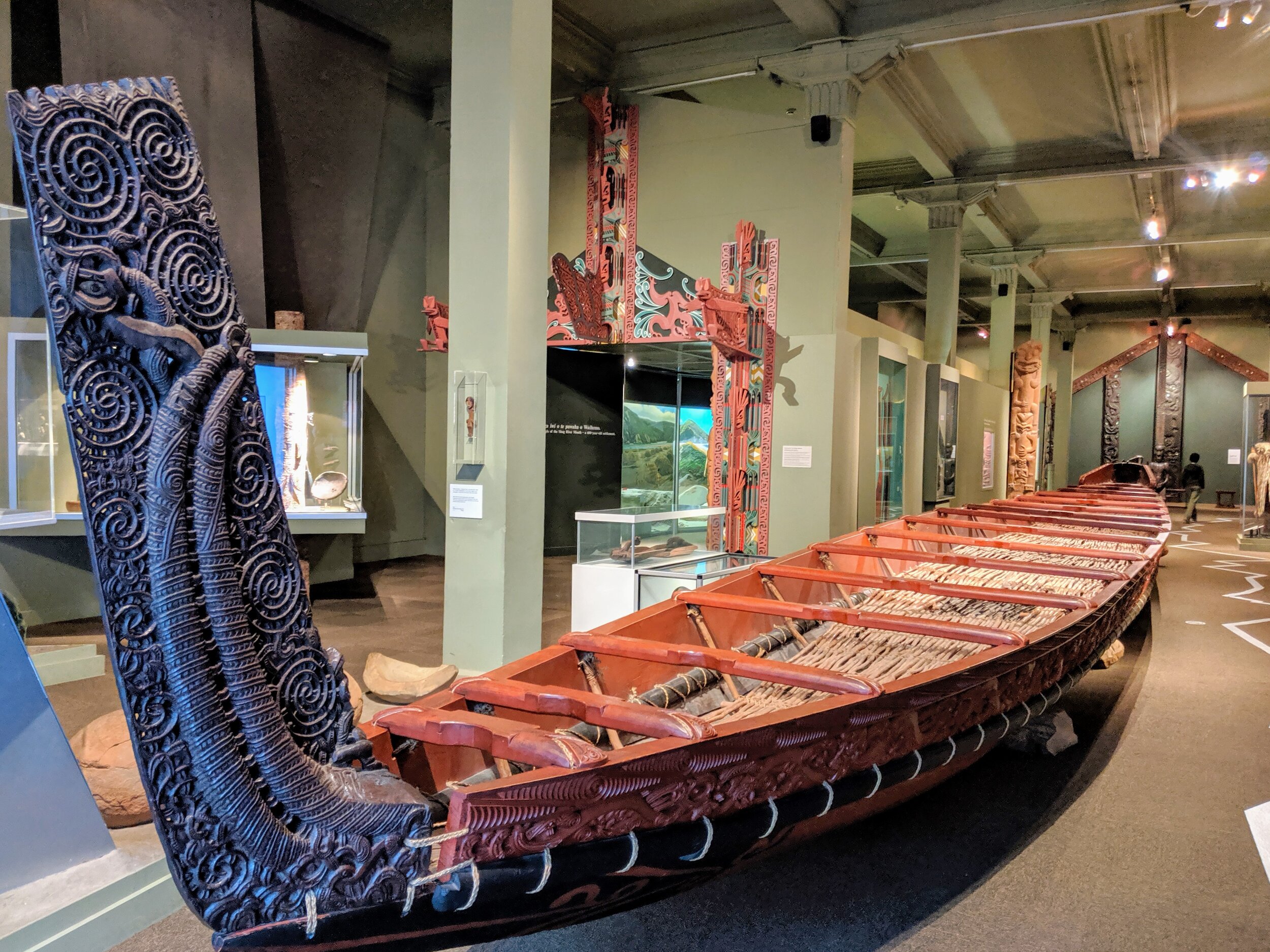

My favorite part of the Otago Museum, which is a natural history museum with a particular focus on the South Island, was the section on the Maori, who are the indigenous people of New Zealand. I had learned a bit about them from my research before this trip and our time in the museum piqued my interest even more. We were all surprised to learn that New Zealand, or Aotearoa (it’s original Maori name), is the last significant land mass outside the Arctic and Antarctic to be settled. The first humans on the islands, descendants of the Maori that came from Polynesia, didn’t arrive on these islands until around 1250-1300 AD. In the grand scheme of human history that wasn’t that long ago. We have commented many times since being here that the country feels very untouched and undeveloped compared to the US and now knowing that humans didn’t even set foot here until 750 years ago we better understand why. My American eyes keep seeing all this untouched beautiful country and being shocked and relieved at how little of it has been developed. Protecting the environment is a constant conversation here and there doesn’t seem to be much of a debate about the effects of climate change. I think when you literally see and feel its effects happening all around you it’s harder to ignore. Changing human habits and making sacrifices in an effort to counteract its effects is part of everyday conversation here. In fact, on our way back from Dunedin we stopped to get gas in a tiny farm town in the middle of nowhere. When I went in to pay the older gentleman at the counter started talking about the odd weather and said he was worried about the rising sea temperatures on the east coast of NZ and how that was impacting weather patterns. I told him that we had just visited Penguin Place and that they were predicting that the yellow-eyed penguins wouldn’t be able to survive much more of an increase in water temperatures and he sadly shook his head. I really appreciate being in a place where most people and communities view themselves as the stewards of the natural world and not the owners who can use it as they please. As with other things, I am curious if these observations hold as we head north and into more populated parts of the country.